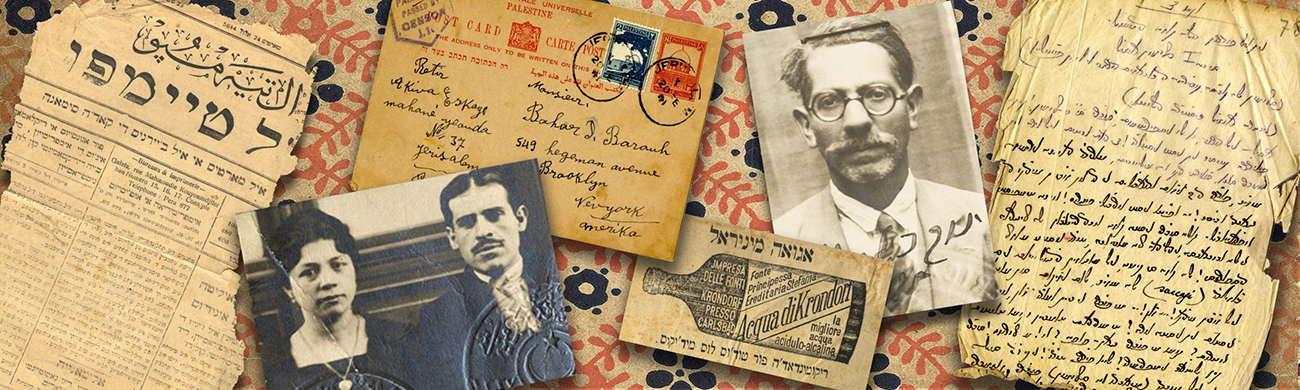

Ladino, the traditional language of Sephardic Jews, is an interesting hybrid. With a Hebrew alphabet and a vocabulary that combines Old Spanish, Arabic, Turkish, and more, it reflects centuries of conquests, expulsions, and migrations. David Bunis, a world authority on the language, has taught Ladino for decades, sharing its intriguing history. But when he taught Ladino at the University of Washington this summer, there were a few surprises.

Bunis, a professor at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, planned to visit the UW to teach. After spending the 2013-2014 academic year at the University as a visiting professor (through the UW Sephardic Studies Program, part of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies in the Jackson School of International Studies), he looked forward to another visit.

COVID-19 dashed those plans. The course was still offered, but with Bunis teaching online from Israel, coordinated by staff members Makena Mezistrano (Sephardic Studies) and Lauren Kurland (Stroum Center). Bunis soon discovered a benefit to the online format: in addition to UW students, he could include students from other universities and members of the Sephardic community.

Bunis taught the month-long course twice this summer, with about 20 students each time. UW students in fields from international studies to physics were joined by colleagues from Columbia and Harvard and other schools in the US and abroad. The mix of participants was exciting, as were their varied reasons for enrolling.

“Several students have family roots connected to this endangered language, but most do not,” says Devin Naar, professor of history and international studies and Isaac Alhadeff Professor in Sephardic Studies, who spread the word about the online course to broaden its reach. “Many come at it with an interest in Spanish, or Jewish studies, or Middle East studies. Some see Ladino as a kind of bridge that connects several seemingly disparate cultures, geographies, and religions.”

A History through Language

The history of Ladino explains its broad appeal. The language arose among the Jews of Iberia and developed under two cultures — the Muslim culture of the Arabs who conquered Spain in 711, and the Spanish Christian culture that took hold in the 13th century. The Sephardic community in Spain maintained its Jewish culture under both groups.

“That was the unifying force,” says Bunis. “Jewish children were taught to read and write in the Hebrew alphabet. Whatever language they were speaking, they wrote it in the Hebrew alphabet. And with each culture overtaking the area, they would incorporate words that worked for them and find alternatives to words they found problematic.”

More upheaval came with the Spanish inquisition in 1478, leading to the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492 and their migration across the Ottoman Empire. “At that point they were in touch with many ethnic groups and borrowed words from each of them,” says Bunis. ”Jewish men were often merchants, so they had to be able to communicate with other groups to do business. And yet they maintained their own group language and identity after the expulsion until our own times. All of those influences make Ladino a fascinating language.”

Ladino continued to be used well into the 20th century in places as far flung as Seattle, New York, Istanbul, and Tel Aviv. But the pressure to assimilate has led many Sephardic families to abandon Ladino, which is now considered an endangered language.

One Course, Many Reasons for Participating

Abby Massarano, a UW art history graduate student of Sephardic heritage, knows all too well why Ladino is endangered. Her great-grandfather, who immigrated to the US in 1916, refused to speak Ladino with his children in an attempt to assimilate into American culture. “And just like that, in one generation, my family’s Sephardic heritage had been erased,” Massarano writes in an essay about her interest in Ladino and the summer Ladino course. “I now have the opportunity, and indeed feel a deep obligation, to reconnect with the language and culture my ancestors knew.”

Guo (Kelsey) Ke, a UW graduate student in music education and ethnomusicology, has no familial ties to Ladino but came to the course with an interest in how Sephardic music traditions are shared in and beyond the Sephardic community. Though she had learned a small amount of Ladino through her doctoral research on Sephardic music, she had no exposure to the Hebrew alphabet prior to the class. “Learning Ladino is a crucial step in my work,” says Guo. “It will greatly benefit my communication with the Sephardic community and my research into written texts related to music and songs.”

Ladino’s mere existence seems to offer a message of connectivity.

Other students were drawn to the Ladino course through an interest in the Ottoman Empire, including several with knowledge of Ottoman languages, which delighted Bunis. “Some of them knew Turkish or Persian or Arabic,” he recalls. “It meant that I could turn to people in the class for discussion of various Ladino words from those languages and how they are used today.”

The Stroum Center was able to offer scholarships thanks to support from the UW College of Arts & Sciences Dean’s Office, with additional support from the Isaac Alhadeff Foundation and the Sephardic Studies Founders Circle. “We hoped to receive 15 to 20 scholarship applications,” Naar says. “We received nearly 60! What this shows is both the strong demand for Ladino language instruction and the paucity of opportunities available. In fact, the UW is the only university in the US offering Ladino instruction during the summer or regular academic year.”

As a result of the course, the Sephardic Studies Program is developing a network of Ladino-interested students and researchers across the country.

“As a hybrid Mediterranean Jewish language with roots in Spain but that flourished in the Muslim world of the Ottoman Empire and is still spoken right here in Seattle, Ladino’s mere existence seems to offer a message of connectivity,” says Naar. “In our current era, which is so fractious and polarized, that can be a powerful message.”

. . .

Hear from more students studying Ladino and learn how you can support Sephardic Studies at the UW.

More Stories

Exploring Connections Through Global Literary Studies

The UW's new Global Literary Studies major encourages students to explore literary traditions from around the globe and all eras of human history.

What the Sky Teaches Us

Brittany Kamai, an astrophysicist with knowledge of Pacific Islanders' Indigenous navigation using the sky, is teaching a new UW course, Pacific Indigenous Astrophysics.

The Truth About Public Speaking

Becoming an effective public speaker requires planning and practice. Professor Matt McGarrity and consultants at the UW Center for Speech & Debate are available to help.