As COVID raged through the Northwest last year, many people avoided infection by staying home. That was not an option for caregivers who spent their days in the homes of others, helping with the tasks of daily living.

This year, geography graduate student Olivia Orosco interviewed Latinx immigrant caregivers in the South King County region to learn about their COVID experience and their work more generally.

Vea esta historia en Español. (Read this story in Spanish.)

“The space of the home is a really interesting site for work — especially in the age of COVID,” says Orosco. “For people who were able to work from home, it was a safe place to be and work. But for caregivers going into others’ homes at the height of a global pandemic, homes were spaces of risk for them, and in some ways for the people they were caring for too.”

The Many Roles of Caregivers

Orosco was working at Tacoma Community House, an immigrant resource center in Tacoma, when COVID emerged. She saw firsthand how the pandemic affected immigrant communities. When a coworker mentioned that her family had contracted COVID through caregiver work, Orosco wanted to learn more.

“I was reflecting on how incredibly risky that must be,” Orosco recalls. “They’re caring for others but then have to go home to their families. I wondered, ‘How do they negotiate that risk? Would they want to talk about this?’ ”

There’s a great deal of nuance when you’re working in a home and your bosses are the person you’re caring for, their family, the home care agency, and the state.

With funding from the UW Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies and the UW Department of Geography's Howard Martin Fund, Orosco was able to devote the summer of 2021 to those questions. The funding freed up time for the research, enabled her to compensate the people she spoke with, and funded a creative component to the project.

First Orosco interviewed caregivers in her coworker’s family, who provided connections to other Latinx caregivers in the South King County area. In all, Orosco spoke with 15 caregivers working in a variety of home settings. Their clients included the frail elderly, people with disabilities, and people with degenerative diseases.

Caregivers attend to the physical needs of their clients — bathing them, administering their medications, preparing meals and coordinating appointments — but also address their emotional and mental well-being. That became particularly challenging during COVID, when clients could no longer participate in activities outside the home.

“A lot of the caregivers mentioned that it was really hard to see their clients’ suffering and loneliness from the loss of that sociocultural element of their lives,” says Orosco. “Often the caregiver was their only contact, since they were not able to leave their home. The caregivers would play music, play games, look through family photos with them — anything they thought would help.”

Learning through Testimonios

Orosco gathered information about caregiver experiences through testimonios — first-person accounts in which the speaker voices their experiences. She felt that approach was important for individuals who are often ignored.

“Testimonios validate the act of listening and acknowledge that active listening is powerful,” Orosco says. “I think giving people an hour and a half of my time to sit and listen has value. It tells them I care about how this year has gone for them, that I want to understand more.”

What Orosco learned: The year has not gone well. Many caregivers contracted COVID from their clients’ visiting family members. Several caregivers were hospitalized with COVID; some have experienced “long COVID” symptoms. Even those with mild symptoms lost weeks of work and risked passing the virus on to their own families.

Beyond the health risks, caregivers expressed frustration at the lack of respect for their profession. They find that clients and the public are largely unaware of the training and continuing education required. Clients or a client’s family sometimes make demands well beyond the scope of the caregiver’s role — and threaten to replace the caregiver if they don’t comply.

“There’s a great deal of nuance when you’re working in a home and your bosses are the person you’re caring for, their family, the home care agency, and the state,” says Orosco. “It becomes quite a complicated web of responsibility and accountability.”

Though they play a key role in the health of their clients, caregivers rarely receive the same recognition as other healthcare workers. One caregiver visited a coffee shop when free beverages were offered to healthcare workers. She showed her badge, only to be informed that she was not a healthcare worker. The disregard for her work stung.

And yet, despite those frustrations, most caregivers told Orosco they love caring for others. Orosco found that to be the biggest surprise in her research.

“It’s physically and emotionally demanding work,” she says. “These caregivers are not compensated well. But every person, even those who had had bad experiences, found a lot of joy and meaning in caring for others. They found pride in helping others live independent lives.”

A Creative "Thank You"

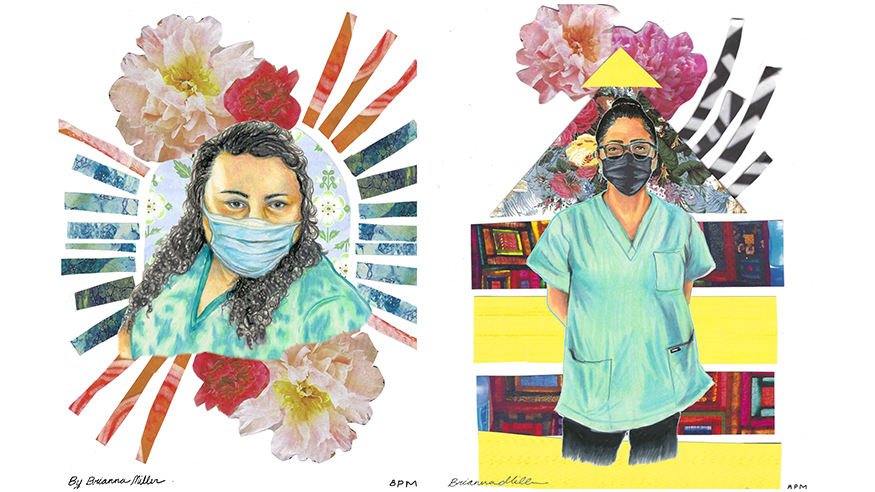

Understanding research to be a reciprocal relationship, Orosco used some of her funding to have artists Brando Martin and Brianna Miller create portraits of the caregivers. Each artwork combines a colorful drawing with a collage background.

“This research is going to benefit me — I’m going to produce a master’s thesis from it,” says Orosco. “I wanted to do something to give back. And I wanted it to be creative because that’s an important part of who I am.”

Each caregiver provided input on their portrait. One asked to have her favorite flower included; another asked that her colorful hair be a central focus. Several chose to be depicted wearing personal protective equipment (PPE). Early on, one identified the spot in her home where she planned to hang the artwork.

Orosco recently delivered the portraits to the caregivers. Finishing her master’s thesis will take a bit longer, but the desire to do right by those who provided testimonios has been motivating.

“They were really wanting to make sure that something came of this research,” Orosco says of the caregivers. “So that’s the pressure on me now. Something has to come of it.”

Each caregiver participating in Olivia Orosco's research project received a portrait created by artists Brando Martin and Brianna Miller.

More Stories

Lifting Marginalized Voices — from Ancient Rome

"Interesting, frustrating, and necessary,” is how Sarah Levin-Richardson, professor of Classics, describes her research into the lives of enslaved individuals in the ancient world.

The Truth About Public Speaking

Becoming an effective public speaker requires planning and practice. Professor Matt McGarrity and consultants at the UW Center for Speech & Debate are available to help.

A Closer Look at Teens & Digital Technology

The impact of digital technology on teens' mental health is the focus of a new course developed by Lucia Magis-Weinberg in the UW Department of Psychology.