Content warning: This article contains references to suicide.

When Leslie Jeanne Berns was born, she was a beautiful, healthy baby. At four months old she had meningitis, followed by frequent ear infections as a toddler. Her parents noticed speech delays and sought help for Leslie. But it would be years before Lacey and Chris Berns fully understood the severity of their daughter's communication challenges or how difficult it would be to get the necessary help.

“The high fever [of meningitis] affected Leslie’s speech and language processing,” explains Lacey. “I compare it to a stroke. Leslie was stuck inside herself. She couldn’t communicate.”

Living on Alaska’s Kodiak Island, Lacey and Chris knew of no other families facing similar challenges. Lacey was tireless in her pursuit of help for Leslie, but she felt she was on her own as she sought appropriate services. The search went on for years. The experience was frustrating and isolating.

“I still get upset, wondering why no one thought to tell me then that the University of Washington has a great program for children like Leslie,” Lacey says. “But there wasn’t a parent support group to share that sort of information. I was in a vacuum.”

To provide other caregivers the sense of community they never had, the Berns recently created the Leslie Jeanne Berns Fund, which made possible a support group at the University of Washington.

A Gift from the Heart

Born into a commercial salmon fishing family, Leslie was a happy child despite her communication challenges. In elementary school she spoke haltingly, with close friends “translating” so she could be understood. The school district provided speech therapy, but it was woefully inadequate for her complex needs. The family came to realize how profound Leslie’s communication challenges were, and how impactful an earlier diagnosis and treatment would have been.

Despite Lacey’s efforts to get help for her daughter in Kodiak and beyond, Leslie’s communication delays continued. She grew more isolated in adolescence, as friends drifted into other social circles. The lack of services in Kodiak’s schools also took its toll. “I felt I was continuing to fight for Leslie, but I was pushing against a huge wall of bureaucracy that didn’t want to provide what she needed,” Lacey recalls.

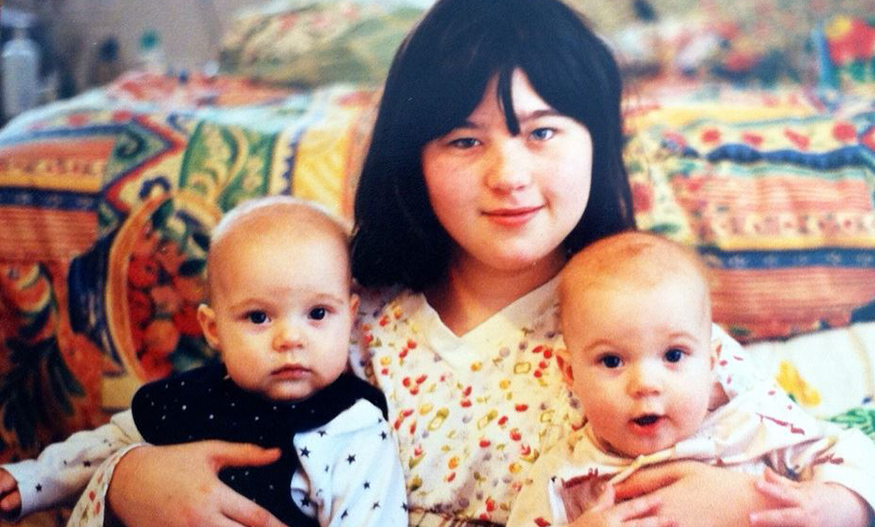

There were bright spots. Leslie was a talented artist and baker. She had a close relationship with her siblings, spending many happy hours salmon fishing with them. But as she reached adulthood, her siblings married and started their own families. Leslie lost hope that she could be like them. She also saw former classmates move on with their lives. Depression set in.

Leslie’s story does not have a happy ending. At age 31, after a decade of mental health struggles, she took her own life. A year later, the family wanted to honor Leslie by making a gift that would help other families facing similar challenges.

With the help of Kelly Schactler, a Kodiak friend and UW alumna (BA, General Studies, 1987), Lacey reached out to the UW Department of Speech and Hearing Sciences (SPHSC) about making a gift in Leslie’s name. Lacey’s initial idea was to support early intervention for communication disorders. But the department already offered excellent early intervention services, so the UW team proposed another option: a support group for parents and caregivers of children with communication disorders.

“I realized that parents would be able to share information and resources, which would in turn help their children,” Lacey says. “A group like that would have been a godsend for me.”

Kelly, who attended the gift discussions with Lacey, felt an immediate kinship with the UW team. “They were so empathetic,” she recalls. “The listened to Lacey’s story, listened to her heart, and generated ideas for what could be done that reflected both departmental needs and Lacey’s vision.”

Becoming Their Own Experts

The Leslie Jeanne Berns Support Group launched in 2020. Meetings continue to be held monthly, open to any parent or caregiver of a child with a communication disorder.

“Communication disorders can be very isolating for caregivers,” says Dr. Amy Rodda, SPHSC assistant teaching professor and director of clinical education, who serves as facilitator. “Parents are navigating a lot of things on their own. Even if they know they’re not the only one going through something, it can feel like they are. To find others who have experienced something similar can be empowering.” She recalls one parent describing the group as “the life vest that can keep us from sinking.”

I realized that parents would be able to share information and resources, which would in turn help their children. A group like that would have been a godsend for me.

As facilitator, Amy answers questions that arise and invites guest experts to speak on pertinent topics. But mostly she encourages participants to talk about their own experiences and share what they’ve learned about available resources. “They’ve become their own experts, which is really wonderful,” she says.

The original plan was to hold support group meetings in person, but COVID meant meeting online instead. That turned out to be fortuitous, as caregivers outside the Seattle area and those with limited availability have been able to participate. The group currently has participants from across Washington state.

Beyond the benefits for participants, the Leslie Jeanne Berns Support Group has been a valuable teaching tool. SPHSC graduate students who choose to attend the meetings gain insights into caregivers’ struggles. It’s a powerful complement to their clinical education.

“Graduate students don’t often get this behind-the-scenes real talk about what it’s like for the families,” says Amy. “The vulnerability that the parents show has been really affecting for our students. It helps them build empathy for the families they’ll be working with when they go out into the field.”

The Berns are thrilled that the Leslie Jeanne Berns Fund — which includes donations from family and friends — is helping others. They also find comfort in honoring their daughter through this gift.

“I want everyone to remember Leslie,” Lacey says. “She was very, very special. It’s so hard to lose a child. You don’t recover. But creating this support group for parents has been a bright spot. It’s been a really good thing for our family to do.”

More Stories

What the Sky Teaches Us

Brittany Kamai, an astrophysicist with knowledge of Pacific Islanders' Indigenous navigation using the sky, is teaching a new UW course, Pacific Indigenous Astrophysics.

A Closer Look at Teens & Digital Technology

The impact of digital technology on teens' mental health is the focus of a new course developed by Lucia Magis-Weinberg in the UW Department of Psychology.

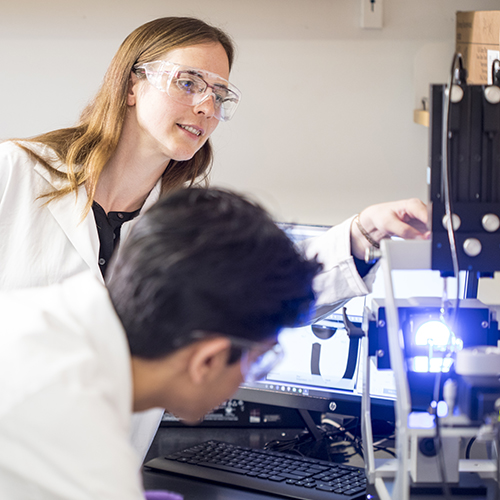

How a Chemistry Lab is Transforming Clinical Research

Ashleigh Theberge's UW lab creates bioanalytical chemistry tools. Some are transforming how clinical studies can be conducted.